Driven by scarcity of modernist masterpieces and a new wave of international collectors, South Asian art is emerging as both a cultural and financial powerhouse.

By Jaswant Lalwani

Most members of the Indian diaspora first encounter Indian art through the modern and contemporary masters such as M.F. Husain, S.H. Raza, and F.N. Souza. Yet fewer still see these works in person, except at major auction houses where they increasingly command global attention. Both Christie’s and Sotheby’s now run dedicated Indian art departments, a sign of how far the category has come. The question, once debated in niche circles, now feels timely: can Indian art be considered a bona fide asset class? Especially given India’s political, social, and economic dominance in the world today.

The numbers suggest the answer is yes. The Indian art market has expanded dramatically — from roughly $2 million in 2000 to about $338 million by 2025. Forecasts project it could surpass $1 billion by 2030. Record-setting sales continue to reinforce this momentum: in 2023, Amrita Sher-Gil’s The Story Teller fetched $7.45 million, while in 2025, M.F. Husain’s Untitled (Gram Yatra) shattered that benchmark at $13.8 million. A rising pool of high-net-worth individuals in India, coupled with a growing domestic appetite for cultural investment — fueled by nostalgia, roots, and heritage — is reshaping the landscape. International visibility is following suit as more Indian artists appear in global auction catalogues, museum exhibitions, and art fairs.

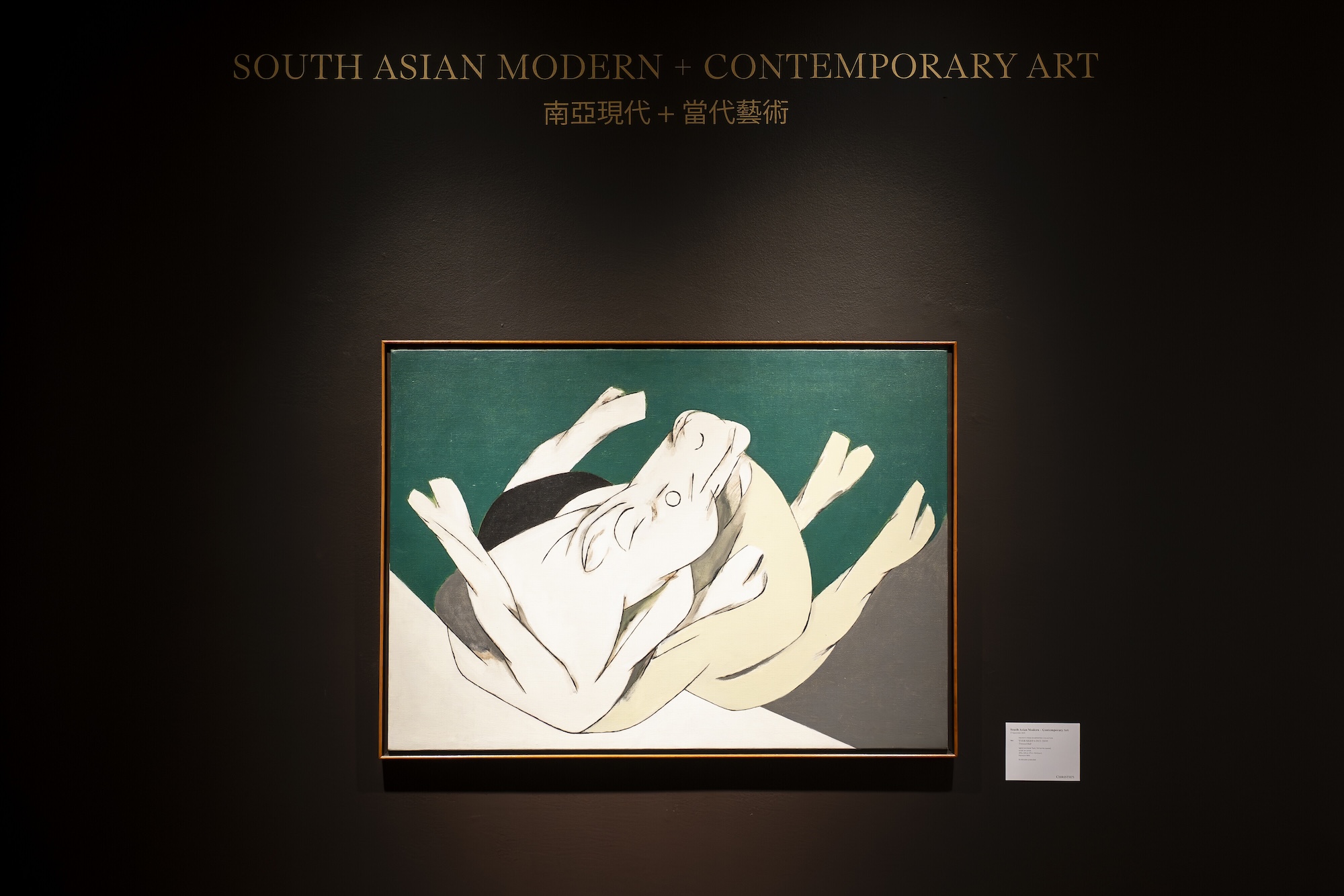

A front-row view of this shift unfolded at Christie’s this fall. Over two days, under the guidance of Nishad Avari, head of the Indian art department, I followed the house’s Modern and Contemporary South Asian Art sale across its 31,000-square-foot facility. Avari pointed out the important — and soon-to-be-important — pieces as we traversed the auction house, adding to the mounting excitement.

Christie’s New York headquarters — the limestone-and-bronze colossus at Rockefeller Center — was electric with the kind of brisk bidding more often associated with European or Impressionist art. The result: a rare “white-glove” sale. All 84 lots sold, totaling $12.38 million, or 150 percent above the low estimate. For a market once considered niche, the outcome was emphatic. Vasudeo Gaitonde’s Untitled (1984) brought in the highest price, realizing $2.4 million.

Sixty works soared past their high estimates; seventy-nine cleared their lows. “It was unprecedented,” Avari said after the sale. “The bidding was extraordinarily competitive on every lot.”

Is the interest global? A collector base once dominated by Indians is now unmistakably international. Buyers participated from India, the United States, the United Kingdom, the UAE, and Singapore — many through online bidding that has redrawn the boundaries of who can access this market. Christie’s first preview in Dubai this season signaled another shift: the Middle East, with its large South Asian diaspora and emerging cultural infrastructure, is becoming a key node. “Collectors today are global citizens, with homes and interests in several countries,” Avari noted. “That mobility has made this market increasingly international.”

Who besides the stalwarts — Husain, Souza, Gaitonde? New names like Sheikh Mohammed Sultan and Ivan Peries set fresh auction records, while works on paper by Rashid Choudhury and Biren De sparked heated bidding. Demand for underrepresented regional artists has broadened tastes beyond the sacred few. The momentum has been steady: earlier this year, Christie’s set eleven new artist records, ten new medium records, and a category record with the $13.75 million sale of Husain’s Gram Yatra.

Although mid-century modernists remain the category’s backbone, contemporary voices are gaining ground. Sculptor Ravinder Reddy and artist Jitish Kallat each achieved more than double their high estimates, while works by Nalini Malani and Sudhir Patwardhan drew strong global interest. Any interest in colonial paintings? Collectors are indeed looking further back in time — late 19th- and early 20th-century depictions of India by Western artists such as Edward Lord Weeks and Marius Bauer, as well as works from the Company School tradition, are finding new appreciation among buyers who previously focused solely on modern and contemporary lots.

With prices rising, can the market sustain over the long term? Avari believes the market is expanding sensibly. Unlike speculative booms that have jolted other sectors, this ascent appears rooted in long-term interest. “Most collectors are buying to hold,” he said. “That makes for a healthier, more sustainable market.” Auction houses have reinforced due diligence — transparency on provenance, condition, and pricing — to bolster confidence. Regulatory constraints add complexity: nine “National Treasure” artists designated by India since 1972 cannot be exported, intensifying demand for works already abroad. Liquidity and shifting import-export policies remain variables to watch, but the market has so far proved resilient.

With masterpieces by the modernists increasingly scarce, collectors are broadening their lens. Second-generation figures such as Arpita Singh, Gulammohammed Sheikh, Bhupen Khakhar, G.R. Santosh, Sohan Qadri, are seeing renewed demand. Christie’s South Asian sales now routinely include Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan, and Pakistani modernists, reflecting both stronger regional markets and collectors’ desire for wider narratives.

This evolution suggests a market graduating from adolescence to maturity. A generation ago, Indian art was regarded as peripheral — promising, but secondary to Euro-American categories. Today, it is widely viewed as an essential segment of global collecting, attracting museums, institutions, and private buyers alike. The challenge ahead for auction houses will be balance: curating tightly to satisfy seasoned collectors seeking top-tier works, while keeping the market open enough for new entrants whose enthusiasm continues to power its growth.

READ: One of New York’s Bravest: A day in the life of an FDNY firefighter (October 21, 2025)

“The depth we’re seeing now is extraordinary,” Avari said. “This is no longer just about the biggest names. It’s about the story of South Asian Art in all its diversity — and collectors around the world want to be part of that story.”

At Christie’s this fall, that story unfolded not only on canvas, but in numbers that answered most questions. Indian art is not just culturally resonant — it is economically viable. Looking forward to the Spring 2026 auction with excitement and hope where I am confident that further reaffirmation of the resurgence of Indian art awaits us.

(Jaswant Lalwani is a global real estate advisor and lifestyle consultant in New York City. He is also an avid writer and globetrotter. To read more of his work visit www.jlalwani.com)