Big banks like JPMorgan and Citi may not be pleased with US President Donald Trump’s latest decision. Reportedly, banks and financial services stocks slid Monday after US Trump called for a one-year cap on credit card interest rates at 10%.

“Effective January 20, 2026, I, as President of the United States, am calling for a one year cap on Credit Card Interest Rates of 10%,” Trump wrote, echoing a pledge he made during the 2024 presidential campaign.

“Please be informed that we will no longer let the American Public be ‘ripped off’ by Credit Card Companies,” he added.

The Review by Ajay Raju: Conspiracy thesis: Is the US strategically devaluing the dollar? (October 27, 2025)

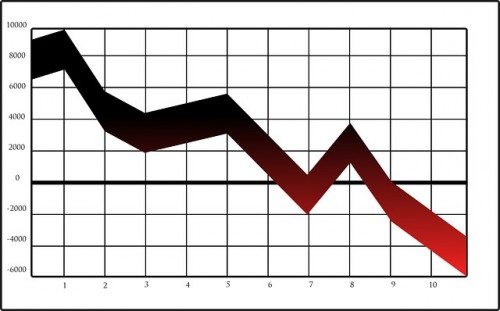

Reportedly, Citi Group lost almost 4% in premarket trading and JPMorgan Chase was last seen down 2.88%, paring some earlier losses. Bank of America fell 2.36%, Visa declined 1.94%, and Mastercard was 2.21% in the red.

A 10% cap on credit card interest rates, if implemented as announced in 2026, would have significant implications for large U.S. banks such as JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup, both of which operate massive credit card businesses that contribute meaningfully to their consumer-banking revenues.

The most immediate impact would be pressure on profitability. Credit cards are among the highest-margin products for big banks, with average APRs well above 20% helping offset credit losses, fraud, rewards programs, and servicing costs.

A hard cap at 10% could sharply compress net interest margins, forcing banks to reassess the economics of extending unsecured credit, particularly to subprime and near-prime borrowers.

In response, large banks would likely tighten underwriting standards, reduce credit limits, or scale back card issuance to higher-risk customers. While JPMorgan and Citi are better positioned than smaller lenders to absorb margin shocks due to diversified revenue streams, the change would still weigh on earnings and could alter growth strategies within their consumer divisions. Banks may also look to raise annual fees, reduce rewards generosity, or introduce new charges to compensate for lost interest income.

From a market perspective, investors would likely scrutinize exposure to revolving credit balances, with potential short-term pressure on bank valuations until the regulatory framework and duration of the cap become clearer. Operationally, banks would also face compliance and system-adjustment costs if pricing structures must be rapidly reconfigured.

Strategically, the policy could accelerate a shift by major banks toward wealth management, corporate banking, and fee-based services, reducing reliance on consumer credit spreads. While JPMorgan and Citi are resilient institutions, a sustained rate cap would mark a structural change to the U.S. credit card business model, reshaping risk, returns, and access to credit across the industry.

Even the announcement alone signals that the government is willing to consider aggressive measures to protect consumers, which may influence investor sentiment and corporate strategy across the financial sector.

For large banks, it highlights the vulnerability of high-margin consumer products to sudden policy shifts and the need for adaptive risk management. The episode also reflects wider economic debates about affordability, household debt, and the balance of power between lenders and borrowers. Beyond immediate market reactions, it serves as a reminder that regulatory proposals, can reshape expectations, pricing models, and long-term planning.

Financial institutions may increasingly diversify revenue sources and reassess exposure to interest-sensitive products, while policymakers and markets gauge the feasibility and potential consequences of such interventions.

Overall, the situation illustrates the persistent interplay between policy, market behavior, and consumer protection in modern finance.