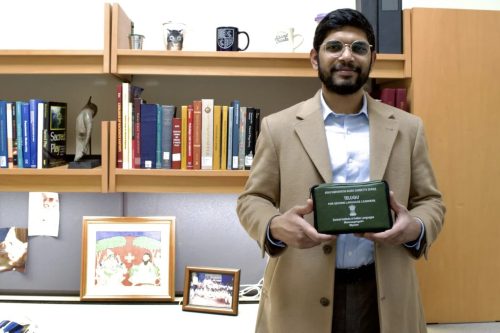

Indian American professor Shiva Sai Ram Urella has launched Yale University’s first program to teach Telugu spoken by over 83 million people across the world and over one million in the United States alone.

It is the fastest growing language in the U.S., yet only a handful of universities in the America offer the language. Yale, now is the fifth university to offer Telugu instruction.

Urella, according to Yale News, is working to make the language more accessible to members of the Yale community and online students from other institutions.

Urella joined Yale as its first ever Telugu instructor in the fall semester, offering Elementary and Intermediate Telugu. This semester, he is teaching Elementary Telugu II, Intermediate Telugu II and an Anthropology course titled “Being and Becoming Hindu: Hinduism Through Ethnography.”

“It’s amazing to see students progress and become more and more confident,” said Urella. “I’m looking forward to seeing how the introduction of Telugu as a language at Yale will plant questions, not just about language learning, but about the very social context of the Telugu speaking region and the diaspora in the U.S.,” Urella added.

READ: Yale’s Shilpa Murthy receives $1.1 million DoD award for cancer research (December 19, 2025)

Before coming to Yale, Urella received his PhD in Religious Studies from Emory University and a Masters in Political Science from the University of Hyderabad.

Urella is a native Telugu speaker who focused his doctoral dissertation on Ogguvandlu, Telangana-based ritual specialists. Urella focused on their common use of turmeric and how their practices challenge the Telangana state’s privileging of written texts.

Urella has a depth of experience speaking and researching the language. But this semester marked his first time teaching the language.

A paucity of teaching materials for early Telugu learners has led Urella to synthesize and workshop teaching materials. Among the resources he utilizes are a textbook written by Velcheru Narayana Rao, the first Telugu chair at Emory University, and a set of cassette tapes issued by the Central Institute of Indian Languages. He also often searches for resources online.

Telugu is an agglutinative language, where words are formed by combining morphemes that correspond to different syntactic features, making it challenging for English speakers to get used to. Moreover, the diverse forms of Telugu spoken today have prompted careful consideration from Urella about how best to teach the language.

“There’s a question of dialect, there’s a question of register, there’s a question of tone, there’s a question of etiquette,” Urella explained. “All of these add to what kind of Telugu it is possible to teach.”

The question of dialect, in particular, is one Urella has been careful to account for. Urella himself grew up in the Telangana region, which he said has its own register of the language. The region’s Telugu has more Urdu, Persian and Arabic influence, and it never became a literary medium. Linguistic diversity exists even among Telugu speakers in the region.

But most Telugu teaching materials are authored by scholars from outside Telangana. Moreover, the Telugu officially used in written documents tends not to reflect all the spoken forms of the language.

According to Urella, the historical reasons for this trajectory are complex and contested. From his understanding, colonial education and print technologies generated the discourse from which the language’s standardization arose.

As a teacher, Urella said he encourages students who grew up with the language to use the terms and grammar they are familiar with rather than forcing them to adopt the exact style he teaches. He tries to incorporate different spellings and pronunciations into his lessons and makes sure not to penalize students for using non-standardized forms.