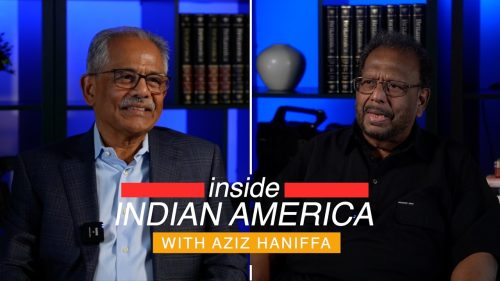

On the debut episode of “Inside Indian America,” Aziz Haniffa chronicles how a Hyderabad-born engineering student — once Barack Obama’s roommate — rose to represent the U.S. abroad and serve across three administrations.

“Sir, Ambassador — welcome to my country. This is the closest I’ll ever get to President Obama, my hero.”

Vinai Thummalapally recounted that moment to me on the debut episode of “Inside Indian America with Aziz Haniffa,” the new American Bazaar podcast series. He had just arrived in Belize to present his credentials as America’s ambassador when a young man ran up, brushed past security, and embraced him — not because of who Thummalapally was alone, but because of what he represented.

Listen to the podcast on Spotify

It was a powerful reminder of how far one story can travel.

As I launched this podcast to chronicle Indian American journeys, I could not have imagined a more fitting first guest. Thummalapally, the first-ever U.S. ambassador of Indian origin, is a former roommate of Barack Obama — back when Obama was simply “Barry,” a college student sharing rent in Los Angeles.

Listening to him describe that embrace in Belize, I was struck by the extraordinary arc of his life. Born and raised in Hyderabad, arriving in the United States at 19 to study engineering, navigating the visa system of the 1970s, building a career in manufacturing, and technology — and then, decades later, receiving a call from a former roommate who happened to be President of the United States, asking him to serve as ambassador.

Watch the podcast on YouTube

In many ways, Thummalapally’s story is the quintessential Indian American narrative: education, entrepreneurship, civic engagement, and public service. But layered onto it is something rarer — the intimate vantage point of having watched history unfold from inside the room.

The former envoy shared with me several stories of his association with the former president, from teaching Obama how to cook dal, to later sitting across from him in the Oval Office discussing diplomatic assignments. It felt like the embodiment of a distinctly American possibility.

Inside Indian America with Aziz Haniffa: Three years that became three decades: Chidanand Rajghatta’s Washington story (February 20, 2026)

And that is precisely why he was a fitting guest to inaugurate “Inside Indian America.” His journey reflects not only personal success, but the evolution of a community—and the expanding idea of who gets to represent America to the world.

Born and raised in Hyderabad, India, Thummalapally’s journey began, like so many immigrant stories, with education.

After high school, he enrolled at RV College of Engineering in Bangalore. But within two years, he made a decision that would alter the trajectory of his life. At 19, he transferred his credits to California State University, Northridge, and arrived in the United States in 1974 to complete his undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering.

It was a different America then — and a different immigration system. On an F-1 student visa, he navigated practical training, graduate school, and eventually employer sponsorship to obtain his green card. Like many in that era, he straddled two worlds: an engineering education that grounded him in technical rigor, and a growing interest in management that led him to pursue a master’s in business administration.

READ: I feel privileged to have had opportunity to give back to United States: Vinai Thummalapally (January 30, 2017)

By the early 1980s, he had stepped into a managerial role in a startup manufacturing compact discs — “CDs,” as he reminded me with a laugh, “which many young people today don’t even know.” From there, his career moved steadily upward. He worked for Warner Brothers, overseeing facilities that produced CDs, DVDs, and Blu-ray discs, then later joined a Japanese firm in Colorado that pioneered data recording processes, eventually leading its U.S. operations.

For nearly three decades, Thummalapally was firmly rooted in the private sector — an engineer turned executive in a fast-evolving technology landscape.

And yet, threaded quietly through those years was a friendship that would reshape his life.

In 1980, while pursuing his master’s degree, Thummalapally shared off-campus housing in Los Angeles with three roommates. One of them was Obama, a young transfer student from Occidental College.

“He was a delight,” Thummalapally says. Back then, everyone called him “Barry.” He was thoughtful, reserved, deeply engaged with philosophy and ideas. He rarely missed a class. “I never leave a classroom if I didn’t understand what was taught,” Obama once told him, explaining how he consistently earned top grades.

When Obama entered politics in Illinois in the mid-1990s, Thummalapally and his wife supported him, as friends do. They attended his wedding in 1992. They fielded phone calls when he decided to run for office. “Who’s going to vote for him?” his wife had wondered in 1995. “He’s such a nice guy.”

History would answer that question decisively.

By 2004, Obama’s keynote address at the Democratic National Convention, when he said “There are no red states and blue states. There is only the United States,” propelled him into national prominence. When I asked Thummalapally whether Obama had written that speech himself, he nodded. “Yeah,” Obama had told him simply.

The rest, as we say, is history.

In early 2009, shortly after Obama’s inauguration, Thummalapally received a call from the new president. Would he consider serving in the administration?

“What do you have in mind?” he asked.

“Ambassador,” said Obama.

Without hesitation, he replied: “It would be my greatest honor.”

Thus began a chapter that would make him the first Indian American ever appointed as a U.S. ambassador. Confirmed unanimously by the Senate, he arrived in Belize in September 2009 to serve as chief of mission.

Belize, a small English-speaking nation bridging the Caribbean and Central America, offered him a new vantage point — not just geographically, but philosophically. Representing the United States abroad, he quickly shed any lingering cynicism about government work.

“I didn’t meet anybody who’s there to collect a paycheck,” he said of his State Department colleagues. “These are people who serve our country with distinction.”

His tenure in Belize focused on strengthening U.S.-Belize trade ties, promoting transparency and democratic governance, and deepening people-to-people connections. It also carried symbolic weight. As the first Indian American ambassador, he understood that young immigrants and children of immigrants were watching.

“I didn’t want to let it go waste,” he said. “With it comes responsibility.”

After nearly four years in Belize, Thummalapally returned to Washington to lead SelectUSA, a newly created initiative within the Department of Commerce designed to attract foreign direct investment into the United States. When he joined, the program had no funding. Commerce Secretary Penny Pritzker secured bipartisan support, and the initiative soon gained traction.

In three years, SelectUSA helped generate over $23 billion in investment from roughly 70 countries. It earned him an unusual distinction: Forbes once referred to him as the “Chief Marketing Officer for the United States.”

Later, under President Biden, he would serve yet again in public service — this time as deputy director and chief operating officer of the U.S. Trade and Development Agency, helping catalyze projects abroad that linked American technology and business expertise to emerging markets.

Three terms of service. Two administrations. One throughline: a belief that public institutions, when staffed by committed professionals, can be powerful forces for good.

Today, Thummalapally channels that conviction into nonprofit work. Through Rural Empowerment, he and partners fund workforce training in economically challenged communities like Danville, Virginia, connecting residents to job opportunities and career pathways.

He is also a founding board member of the South Asian Impact Foundation, which supports South Asian Americans running for public office. In 2017, there were roughly 48 South Asians in elected positions nationwide, he noted. Today, that number exceeds 350.

The arc is unmistakable.

As we wrapped our conversation, I asked him about his friendship with Obama. The two remain in touch, though sparingly. After Thummalapally’s father passed away earlier this year, Obama called him personally to offer condolences. Weeks later, they met and spoke for nearly an hour — “just talking like we were talking 40 years ago,” he said.

Once, riding in a golf cart, Thummalapally addressed him as “Mr. President.” Obama tapped him on the thigh and said, “You can call me Barack.”

It is a small anecdote, but it captures something essential: groundedness amid history.

Thummalapally’s story is not just about being the first. It is about possibility. It is about how an immigrant student from Hyderabad, who once split rent in Los Angeles, could rise to represent the United States abroad. It is about friendship that survives power. It is about service that transcends administrations.

And perhaps most of all, it is about the evolving idea of America itself — an idea that, in the words of a young woman in London who once paid to hear Obama speak, still gives people “hope for tomorrow.”

In telling Thummalapally’s story, I am reminded why I began this podcast in the first place: to capture journeys that illuminate not just individual achievement, but the quiet transformation of a community — and a nation.