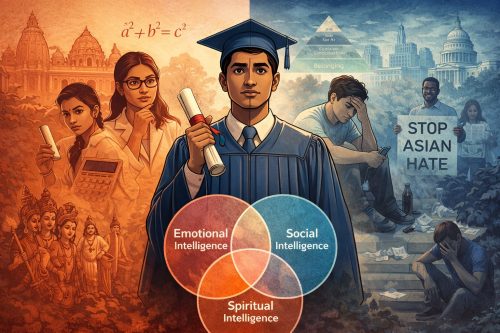

Indian Americans have mastered academics and careers, but struggle with the emotional and social intelligences required to feel fully at home in America.

We like to tell ourselves a comforting story about intelligence, especially within the Indian diaspora — a story reinforced by test scores, spelling bees, engineering rosters, and the quiet pride of parents who crossed oceans armed with degrees and discipline. By most conventional measures of cognitive intelligence, we have done extraordinarily well.”

Yet the deeper and more uncomfortable question is whether intelligence, as we practice and value it, has become dangerously narrow, optimized for exams and credentials while remaining underdeveloped in the domains that actually govern belonging, judgment, empathy, and moral navigation in a complex society.

If intelligence is the ability to adapt to one’s environment, then it is worth asking whether Indian Americans are truly adapted to American society or merely successful within carefully constructed corridors of it, moving efficiently between classrooms, boardrooms, exam rooms, temples, and dance halls while remaining strangely detached from the emotional, social, and cultural undercurrents that shape the lived reality of the country we inhabit.

READ: Sreedhar Potarazu: Upside-down food pyramid: When nutrition advice ignores economic reality (January 8, 2026)

Emotional intelligence, social intelligence, and what some would call spiritual intelligence are not ornamental traits but the very capacities that allow individuals and communities to read the room, sense unspoken norms, understand suffering that does not look like their own, and respond to moral ambiguity without retreating into dogma. To be clear, I am not claiming to have mastered these forms of intelligence, and am on my own personal journey of understanding

Many Indian families arrived in the United States with a survival mindset forged by scarcity, hierarchy, and reverence for authority, and those instincts served a purpose in a different time and place. Yet, when transplanted unchanged into a society defined by individualism, pluralism, and constant renegotiation of identity, they often produce generational dissonance rather than cohesion, because children raised here are navigating drugs, gender identity, race, crime, and justice systems that their parents neither encountered nor were prepared to understand, and when those conversations are avoided, minimized, or moralized rather than explored, the gap is filled not with wisdom but with silence, shame, and confusion.

This is where the conversation about multiple forms of intelligence becomes unavoidable, because cognitive intelligence may help a child ace calculus, but it does little to help a teenager process depression, resist destructive peer pressure, or understand why a classmate might sell drugs to put food on the table.

When communities lack the emotional literacy to discuss these realities without fear or judgment, they do not disappear; they simply move underground, where isolation deepens, and misunderstanding hardens into quiet contempt for a society that feels foreign despite being home.

READ: Sreedhar Potarazu | America at 250: We The People: The common thread (January 1, 2026)

Daniel Goleman’s work on emotional intelligence offers a useful lens for understanding this imbalance, because he argues persuasively that self-awareness, emotional regulation, empathy, and social skill are not soft traits but core competencies that determine how individuals function in families, communities, and leadership roles, and when these capacities are underdeveloped, high cognitive ability can actually magnify dysfunction rather than correct it.

In many Indian American households, emotional restraint is often mistaken for emotional maturity, obedience for self-regulation, and silence for strength, creating environments where feelings are managed through suppression rather than understanding, and where difficult conversations about identity, suffering, or moral ambiguity are postponed indefinitely.

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, a framework many high-achieving communities rarely pause to examine, clarifies where this imbalance may be occurring, because while many Indian Americans have successfully secured the lower tiers of the pyramid — physiological stability, safety, and economic security — we often assume that this automatically propels us upward toward belonging, esteem, and ultimately self-actualization.

In reality, belonging cannot be engineered through proximity to cultural institutions alone, esteem cannot be sustained solely through credentials, and self-actualization is impossible in the absence of emotional integration and moral coherence, leaving many individuals suspended at a plateau of material success without the deeper sense of purpose, social embeddedness, or psychological wholeness that Maslow envisioned.

The result is a peculiar form of isolation that masquerades as cultural preservation, where temples, cultural associations, and social circles become safe enclaves rather than bridges, and while there is nothing inherently wrong with preserving tradition, problems arise when these spaces become substitutes for engagement rather than platforms for it, reinforcing an inward gaze that limits exposure to the very social complexity required to develop empathy, civic understanding, and moral courage in a diverse democracy.

READ: Sreedhar Potarazu | Healthcare year in review 2025: Key trends, challenges and shifts (December 29, 2025)

This raises an uncomfortable but necessary question about integration, because integration is not assimilation, nor is it cultural erasure, but it does require the capacity to understand lives radically different from one’s own, including the pain of poverty, the logic of desperation, and the structural forces that shape crime and injustice. Without that understanding, political participation risks becoming abstract, performative, or disconnected from the realities of those most affected by policy decisions.

So when we ask whether we will ever see an Indian American president, the more important question is not electability but empathy, because leadership in a pluralistic society demands more than résumé brilliance, it demands the ability to sit with discomfort, to recognize suffering without reflexive judgment, and to speak credibly to communities whose experiences cannot be reduced to effort or merit, including the person living in poverty, selling drugs not out of moral failure but out of constrained choice.

If intelligence is truly multidimensional, then the challenge before Indian Americans is not to prove how smart we are, because that argument has already been won, but to confront how incomplete our model of intelligence may be, and to ask whether we are willing to cultivate emotional fluency, social courage, and spiritual depth with the same rigor we apply to academic success, or whether we will remain a community admired for achievement yet distant from the society we claim as our own, suspended between worlds, highly capable, profoundly unsettled, and still searching for a place that feels like home.

1 Comment

Thank you. Dr. Potarazu for the article. I can relate to it personally.

As recently neutralized US citizen (two years back), who immigrated to this country at age of 23 and living here since past eight years, I have very good carrier/job in Tech and finical success in relative short time. I am firsthand experiencing, the point you raised about sense of not belonging. The success feels empty and me isolated in county of 300M+ people.

During first two years in US, I did master’s here it helped little bit to understand the workings of US society, but it was also full of Indians – 80%. After that I have surrounded myself mostly with Indians (@work, family, area that I live in etc.), which in turns not helping in integration/assimilation or developing sense of belonging.

Not to become first Indian American president, but more assimilated citizen with fulfilling life, I agree with your points about willing to cultivate emotional fluency, social courage, and spiritual depth with the same rigor. But can you shed light on how to do that?

The general advice would be to go out and interact with other people, but when you are surrounded by same community at work, home, temple, friends and late in the life, it is easier said than done. Do you have any suggestions or more concrete advice?